FIRST AND FOREMOST, DOUBT

Ángel Calvo Ulloa

This text was writen for MIRROR RIM (Bilbao, 2020) publication and was published with the text Painting Through the Looking Glass by Carolina Puigdevall Claver.

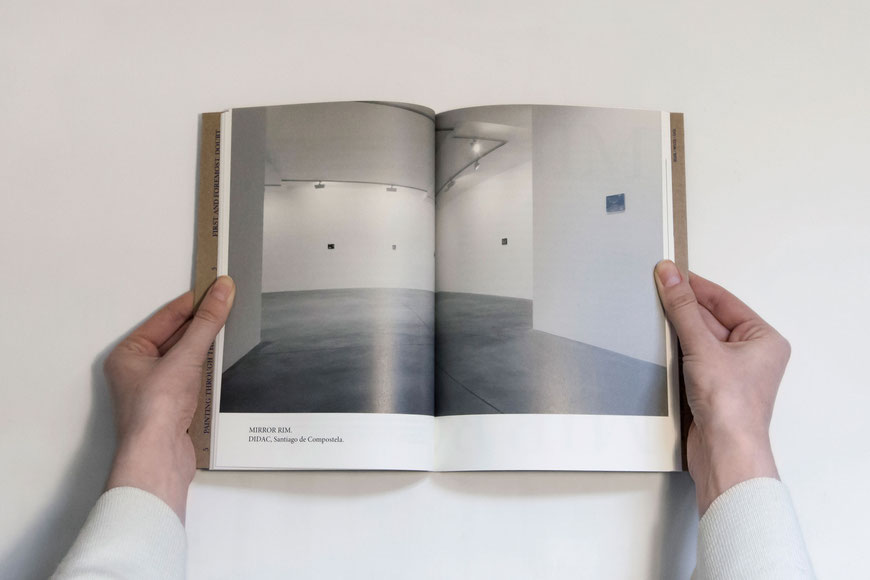

Mirror Rim took place at the DIDAC Foundation (Santiago de Compostela) between December 17 and January 28, 2018 and at Appleton Square (Porto) between May 16 and June 16, 2018

If there’s one thing that still seems enigmatic to me today about Alain Urrutia's painting, it is not, of course, his painting style, or his technical ability when doing his work. Those things, as with any good painter, are linked to a series of practised skills that, over time, can produce impeccable technical ability and yet have little or nothing to do with excellence. What continues to seduce me is his ability to select moments, the skill of a watchful gaze that is able to disconnect fragments from a single situation, turning them into mysterious pieces of a scene that may not, a priori, appear unusual or unfamiliar to us, but which the artist is able to isolate to the point of abstraction. Merely standing in front of one of his small paintings and turning away with more doubts than certainties is what still captivates me. It's probably the same magic that brings us to fantasise about sneaking into the painter's head and looking out through his eyes, desiring at times to guess whether an isolated fragment of the reality that surrounds us is our mistaken way of understanding what he is extracting or if, on the contrary, it could be worthy of becoming part of his repertoire.

I remember when Alain visited me in Oporto in 2010. I was spending a few months in the city as an errand boy, as part of a project that was being unpredictably undertaken all around a city that was at the time unknown to me. We travelled together to Lalín, chose the location for an intervention that he would carry out nearly a year later, and talked about a text that I had to write for El quinto en discordia.[1]With Alain, work and friendship have always gone hand in hand. Always attentive to everything that goes beyond painting, he is a solicitous listener with those who, like me, have carved out a relationship to him that is both personal and professional.

For all the time I have known him, nothing in Alain Urrutia has tended to seek out that stability which almost every artist aspires to. When things seemed finally to be going well, conducive to his being able to drowse in the comfort of his own studio with central heating and double-glazed windows, he decided to go off to London, where he lived for years as an expatriate artist, finding refuge in a work routine that had already been characteristic of him and tightening his belt to be able to pay for a small studio just a few kilometres from his house—a distance that, as part of his routine, he travelled by bicycle every day. That allowed him, perhaps, to keep himself prudentially separated from his workplace, preparing his arrival during the journey and, at the end of his workday, putting off his departure from that universe that surrounds the studio of all painters. All this could seem anecdotal were it not for the importance that that tendency towards discipline and rigour has had even today on the development of his artistic career—and they have been decisive in his approach to painting. The transcendence that a series of daily acts acquire as a result of repetition, and his attitude when facing the world, have gone along having an effect on his work, on his time and that of the viewer—as well as on his relationship with the people who surround him. Evasive with regard to almost everything that’s ever threatened to tie him down, Urrutia is nonetheless an individual who—as friend or painter—has always been there. Perhaps that is why being given the task of writing about his painting acquires a complex dimension that inhibits me when attempting to separate out from the Alain whose gaze and decisions seduce the Alain Urrutia whose earnestness and nobility are decisively related to his artistic proposals.

In 2015, when he was preparing 20 minutos de pensamiento abstracto[2](20 Minutes of Abstract Thought), Urrutia's painting began developing a reduction in the size of its images, scaling down details, establishing a closer, more individualised link with the viewer, who, suddenly, became the sole receiver of his pieces. Along with that decision, the relationship painting was going to have with space from then on had to be rethought as well, with him opting to produce based upon the place where the paintings would go—not abandoning his tendency to produce for specific contexts but substantially changing what would be required of each location from that moment on.

It should be clarified that that type of decision, a decision affecting the matter of scale and its relationship with all the different exhibition spaces, has always been present in Urrutia's work, generating interconnections and working on the importance that each image has, nearly always reinforced by its diminution, in order to go back to that much-sought intimacy offered to us by knowing ourselves to be—just for a moment—the only gaze that settles upon a thing. That's why the larger-scale paintings that Alain has been presenting have always seemed less enigmatic to me; not wanting, of course, to downplay them with that statement, since I understand that all installations are normally made up of high points and points of transition, perhaps easier to digest so as to make the visit more fluid.

The broad repertoire of images that have made up his painting since he started his career in 2008 has a close relationship, in the first place, with his interest in visual culture, given to him by art history, but also with his deep political nature, itself not free of a visual culture equally powerful, which has gone on along intermingling with the constant allusion to painting from within painting and to his particular imaginarium stemming from ordinariness, which somehow narrates what his life has been until today. In 20 minutos de pensamiento abstracto, the images came out of that visual repertoire linked to art, and the titles of each of those small pictures were taken from ones that Beethoven gave to some of his thirty-two piano sonatas. Urrutia then took a step forward, linking his images with a title that included a factor initially external, justified by the pretext of their having been the pieces he listened to while painting the pieces. Composed between 1793 and 1822, those sonatas—in addition to their clear importance for musical history—were part of Beethoven's production during troubled years for European politics. Simultaneously, the composer himself—influenced by the changes that were taking place and not needing to, for example, put on recitals in the halls of the courts to survive—became an individual who operated with unheard-of independence and sympathised with the revolutionary cause. Perhaps, in an unpremeditated way, he could not help but decipher a vestige of self-referentiality in all this, I have no doubt, just as I also have no doubt about the indivisible relationship that Urrutia has been able to establish between each of his paintings and the musical composition whose name it bears, generating a sudden series of unparalleled links that affect images and sonatas separately. Those nine small canvases marked, in a way, the start of an unexpected turn in his work—something that continues to be hashed out in his studio which, true to the artist's natural bent towards change, is now located in Berlin. These lines, then, serve to clarify the importance that that exhibition entitled 20 minutos de pensamiento abstractohas had in relationship with the matter we will now tackle. The decisions that affected that series were effectively an evolution in the way in which Urrutia’s formal and conceptual development had been shaping up since 2008, reaching an apex of maturity in 2015.

En 2017 DIDAC le propuso realizar una exposición a dos sedes, primero en la que esta fundación regenta en Santiago de Compostela, y acto seguido en el espacio de Appleton Square, en Lisboa. Sujeto a ese diálogo con los diferentes espacios para los que ha ido trabajando de un modo específico, el proyecto comenzó a armarse a partir de un esquema que, como en el caso de 20 Minutos de Pensamiento Abstracto, nacía de un croquis que interconectaba conceptualmente todas las escenas elegidas. Éstas, surgidas de un interés por el retorno de la imagen reflejada, nacían del encuentro fortuito de un pequeño espejo en los primeros días de su llegada a Londres. Sobre él, situado en su mesilla de noche, de un modo improvisado, Urrutia fue depositando cada día sus llaves, monedas y todo lo que se había ido acumulando durante la jornada en sus bolsillos, hasta que alguna de las imágenes devueltas por aquel espejo lo llevó a dar el paso de fotografiar sistemáticamente las simetrías provocadas por su reflejo. El hecho rutinario y azaroso se convirtió entonces en una búsqueda y, a continuación, los objetos fueron perdiendo ese carácter aleatorio, estableciendo una complicidad con el espejo, implantando unas pautas y buscando el equilibrio de la composición. Para Mirror Rim-el borde del espejo-, que así se tituló, Urrutia echó mano de ese conjunto de fotografías que se habían ido acumulando en su disco duro, y entonces comenzó a trazar un plan que de nuevo las envolviese, vinculándolas conceptualmente para tejer una historia improbable, por medio de un repertorio basado en sus notas acerca de las simetrías que producía el reflejo, y a propósito de la singular magia que históricamente ha rodeado a estos artilugios.

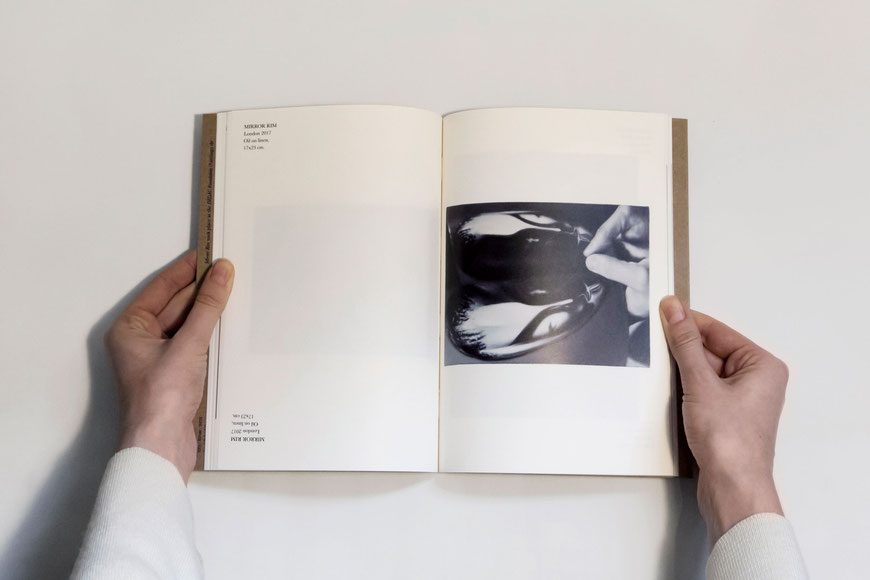

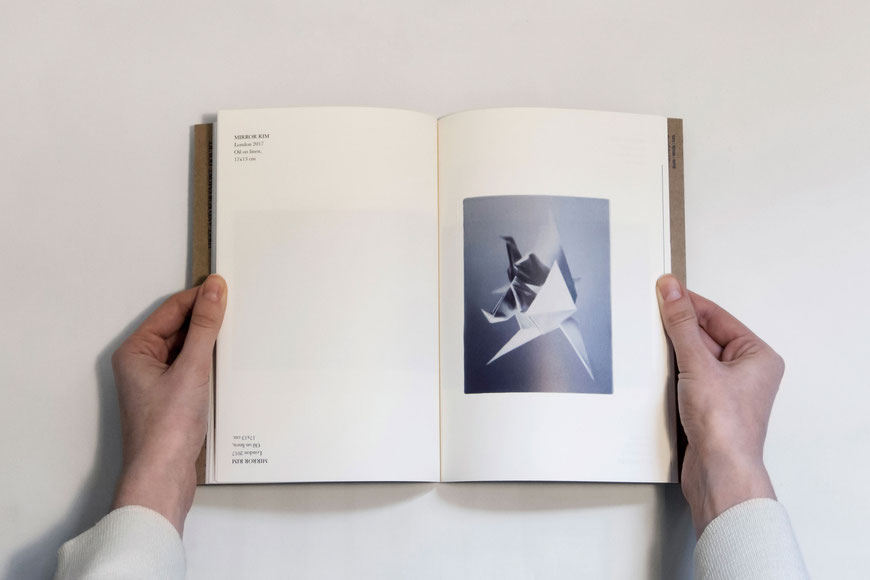

In 2017, DIDAC proposed for him to undertake an exhibition in two venues; the first at the place that foundation calls home, in Santiago de Compostela, and then in the Appleton Square cultural space in Lisbon. Subject to that dialogue with the different spaces, with each of which he’d been working separately, the project began to come together based on a framework that, as in the case of 20 minutos de pensamiento abstracto, was born of a sketch connecting all the selected scenes conceptually. Those scenes themselves, arising from an interest in the return of the reflected image, came out of a chance meeting with a small mirror during the first days after his arrival in London. Atop that mirror, situated on his bedside table, Urrutia left his keys, coins, and anything else he had accumulated in his pockets during the day, doing so until one day the images that mirror returned led him to systematically photograph the symmetries the reflections brought about. That routine and random action thus turned into a quest and, subsequently, the objects began to lose their random character, with a certain complicity being established with the mirror, implementing guidelines and seeking balance in the composition. For Mirror Rim—as the exhibition was titled—Urrutia pulled out the set of photographs he had gradually accumulated on his hard drive and then began to draw up a plan that would envelop them once again, linking them conceptually so as to weave an improbable history through a repertoire based on his notes on the symmetries the reflections produced and the singular magic that has historically surrounded these contraptions.

A visit to that exhibition confirmed all prior hunches. The ample space at DIDAC had, leading from the door, a succession of ellipses, up to eleven, although not all of them could be seen from a single position. That initial visual blow was far from what those walls seemed to demand; the proportions, however, were perfect. A certain initial visual contact was produced, and urged one to delve deeper. Each image created a distance between us and it, always the same, and a lapse on the wall that was similarly repeated. In front of each one, only that one was contemplated, the next one waited its turn, and so on down the line. Mirror Rimmade its presence felt and kept its splendour when the paintings were rotated in Lisbon. The poster had already advanced it, but actually being able to see how the exhibition could work upside down was thought-provoking.

Analysing them now, the images the mirror returned in Mirror Rimemphasise the links that Urrutia creates with art history. Relationships that are not at all obvious, that associate—for example—the painter's reflected hand with the hands Caravaggio painted for his Narcissus; or one of the pyrite stones that Urrutia collects can be seen in the mirror as inevitably referring to the alunite that Dürer included in his engraving entitled Melencolia I,and which has become, throughout history, a constant resource because of its strangeness and the doubts it sparks about its true function. One after another they gradually appear, each one based on a link that is not at all self-evident; seductive, perhaps, more because of what they hide than what they tell. On top of all that, as a postscript, there is a nod that—without any need to rotate two of the pieces a hundred and eighty degrees, just exchanging their positions on the wall—places the portraits of two identical twins front to front or back to back.

Palindromic, this project maintains, by means of the images that make it up, that doubt about the true nature of reflection; that mistrust Alice also had when she looked through the looking glass, wanting to get beyond it to find what truth there is in what the reflection returns.[3]In Mirror Rim, that return intentionally breaks its symmetry by acting directly upon the photographic frame itself. Urrutia will play with the perspective of the mirror, then, or with the possibility of showing—with the help of the mirror—parts of an object that would otherwise remain hidden. What truth is there, then, in all of this?

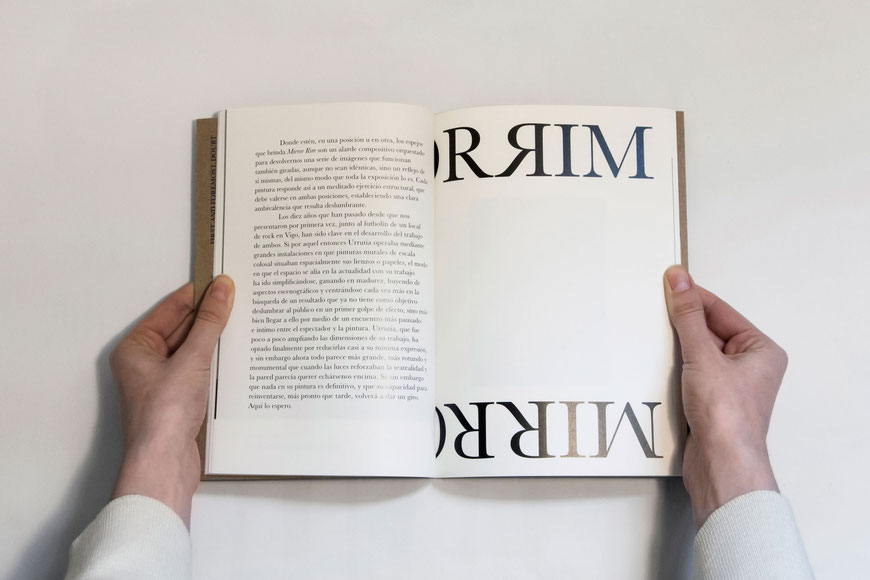

Wherever they are, in one position or another, the mirrors that are provided by Mirror Rimare a compositional display orchestrated to return to us a series of images that also work rotated, even if they are not identical but instead a reflection of themselves—just like the exhibition as a whole. Each painting thus represents a meditated structural exercise that must work in both positions, establishing a clear ambivalence that is dazzling.

The ten years that have passed since we were introduced to each other for the first time, next to the foosball table [or “table football” for Brit?] at a rock bar in Vigo, have been key in the development of the work of both. While Urrutia operated then by means of large installations in which mural paintings of colossal scale spatially defined his canvases or papers, the manner in which space is allied with his work today has been simplified, gaining maturity, fleeing from scenographic aspects and focusing more and more on the search for a result whose aim is no longer to dazzle and delight the public with a first shock effect but, rather, to reach the public by means of a more gradual, intimate encounter between viewer and painting. Urrutia, who gradually expanded the dimensions of his work, has ultimately opted to reduce his paintings to almost their minimum expression and, nevertheless, now everything seems bigger, more resounding and monumental than when lights reinforced the theatricality of it all and the wall seemed to want to topple down onto us. I know, however, that nothing in his work is definitive and that his ability to reinvent himself will, sooner rather than later, again come into play. I'm expecting him.

[1]El quinto en discordia(named after the book 'Fifth Business,' by Robertson Davies) was an exhibition planned by Alain Urrutia for the months of January and February of 2011 at Ariz Towerin Basauri.

[2]The exhibition 20 minutos de pensamiento abstractotook place at the Casado Santapau Gallery (Madrid) between March 17 and April 30, 2016.

[3]Oh! I do so wish I could see that bit! I want so much to know whether they’ve a fire in the winter: you never can tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up in that room too — but that may be only pretence, just to make it look as if they had a fire. Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass.